- Past

-

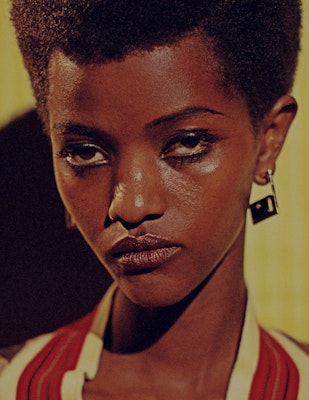

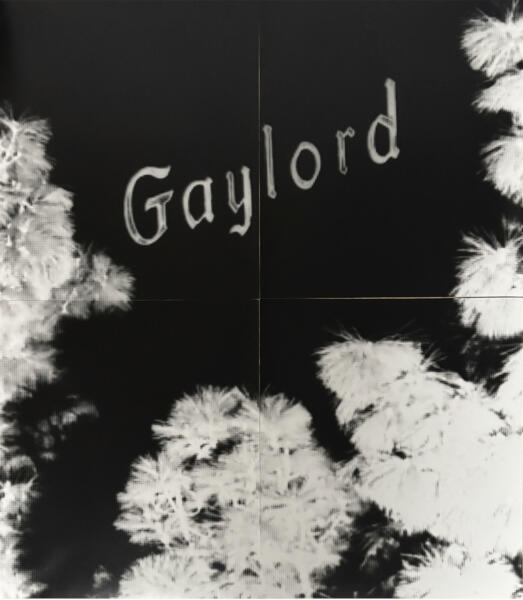

Robbie Lawrence,

Mann

![]()

-

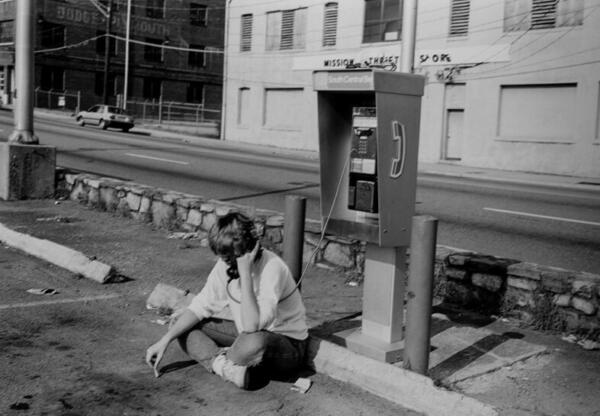

Timon Benson,

Voice of Matter

![]()

-

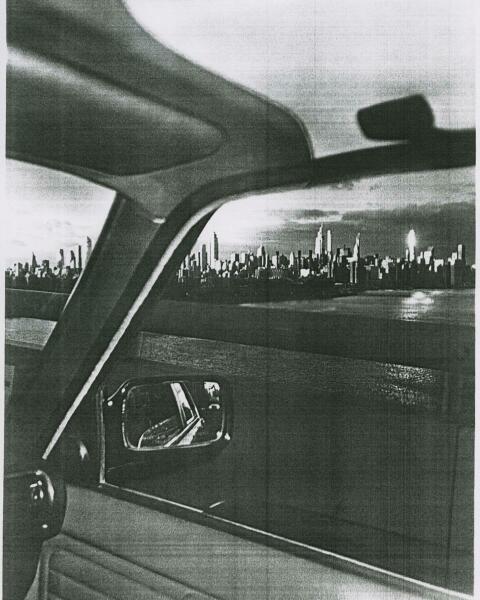

Yale MFA Photo,

First Breath Second Sight

![]()

-

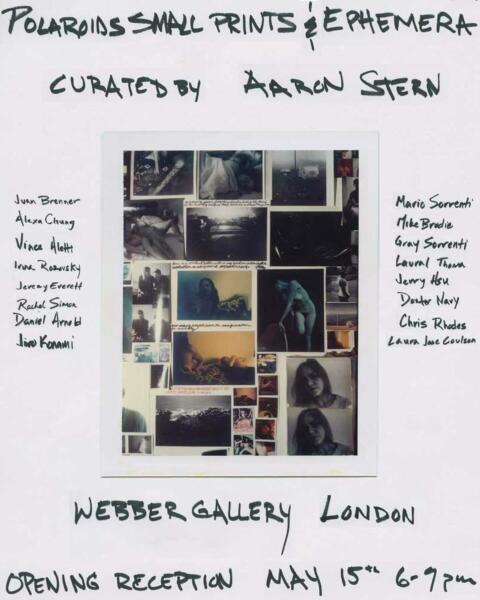

Aaron Stern,

POLAROIDS, SMALL PRINTS and EPHEMERA

![]()

-

Yorgos Lanthimos,

Photographs

![]()

-

Webber Gallery,

Photo London 2025 Stand G17

![]()

-

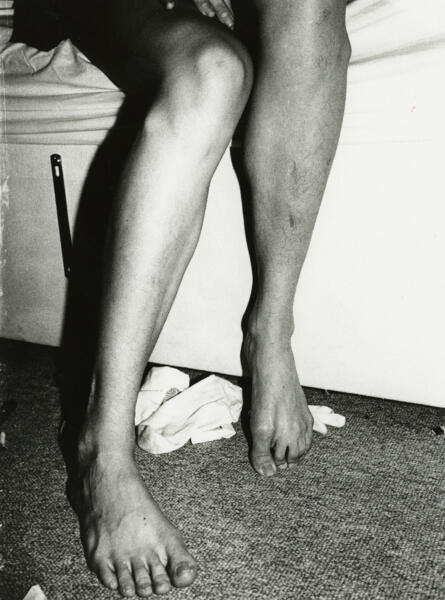

Peter Tomka,

Bachelor Suite

![]()

-

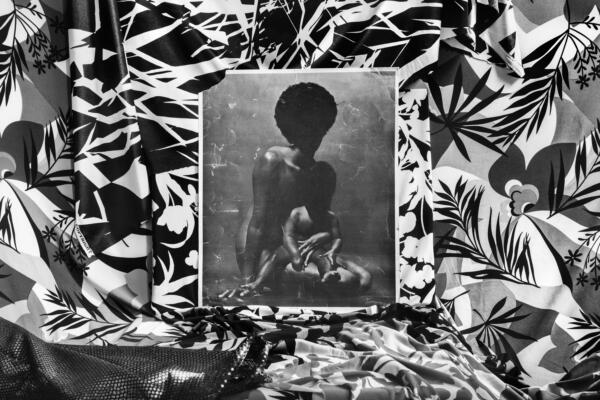

Keisha Scarville,

lick of tongue, rub of finger, on soft wound

![]()

-

Aaron Stern,

Hard Copy Los Angeles

![]()

-

Pia-Paulina Guilmoth,

Flowers Drink the River

![]()

Thomas Albdorf

Mirror Mirror

19 September – 3 November, 2019

Museum Folkwang

Museumsplatz 1

45128 Essen

Germany

Thomas Albdorf in conversation with Thomas Seelig, Head of the Department of Photography at Museum Folkwang, Essen.

Thomas Seelig: In “Mirror Mirror” we show two work groups from your more recent oeuvre, each accompanied by publications. Can you briefly outline your areas of interest over the last few years?

Thomas Albdorf: The first book from 2015 is entitled “I Know I Will See What I Have Seen Before”. It deals with Austria, my home country, and the way it is depicted. I am interested in how Austria is constructed through images, and how we as Austrians imagine our country, and how we are seen from the outside. The reason for this was that I had been looking at Austrian Heimat films and had seen how Austria was repositioned shortly after World War II via these sentimental renderings of the country and its regions. There was a historical denial of the war. The Heimat films are set before it, so the war hadn’t taken place, so to speak. Everything is beautiful, everyone runs around happily in the mountains and loves each other.

So for the book I drove to the Austrian mountains to take some – to my mind – relatively conventional landscape photographs. Then I went to the studio and deconstructed them in various ways: partly pre-photographically and partly post-photographically. At first, the book begins in the classical style, but later some subjects appear that are not immediately accessible. Then there are some pictures that have quite obviously been reworked and “faked” to a greater or lesser extent. And then there are some more plausible images again, and so it goes on.

TS: Almost immediately after that you began work on your next project “General View”, which is not part of this exhibition. What was this work based on?

TA: It’s based on the assumption that I can also apply the method I just described to landscapes that I have never visited myself. I have a passion for famous American national parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite. Back in 2014/15, I discovered that you could do a pretty accurate tour of Yosemite using Google Street View. Just like with a car, you can take an imaginary drive along the system of roads in the park, which is pretty well developed. The Google Street View camera also went off-road and was mounted on a backpack and sent off on a selection of hiking trails through Yosemite. So, I could view the park in very abstracted way up to a point. On the basis of this information, I got to work and contacted agencies to buy pictures taken by other photographers. It was interesting to see how these great American landscape photographers had depicted the park. Incidentally, most of them were indeed photographers – old white men, in other words. There was an author in the UK who wanted to write about my book and who had believed, right up to the moment he interviewed me, that I had actually taken the photos on-site. He said he wouldn’t have thought it possible for every single picture to have been created in the studio.

TS: How do you make your images? Just working on the computer? Or do you simulate reality in some other way when you create, say, the picture of a waterfall?

TA: I do some of the work on the computer, but most of my images are pure products of the studio. In practice, I build something with my hands there and then photograph it. I use cheap special effects, so to speak.

TS: What was your next project?

TA: The third group of works from 2018 is called “A Miss Is As Good As a Mile”. This time I imagine a journey to an unspecified place, which could be somewhere on the Mediterranean. In other words, it doesn’t show something concrete happening in Italy or Spain or Greece or Turkey, but it’s more about certain ideas we have about holidays by the sea. At the core of this group of works, I was interested in deconstructing the software that analyses images and creates new images based on what it “knows”. In the video “Flowers Were Waiting on the Balcony of the Room, So Beautiful!”, for example, I placed a vase of flowers on a revolving pedestal and filmed it in front of a photograph of the sea in the background. Because it has been processed in post-production, the video also shows the view as “seen” by the software. In this series I work primarily with Photo- shop, a tool that can analyse an image and replace parts of it.

TS: To what extent did you “train” the software?

TA: The software has its own knowledge and functionality, so I can’t train it. However, I do refer to contemporary image analysis and image creation processes, which are becoming an increasingly significant part of our everyday lives. Computer networks consisting of two elements – a network that has knowledge about, say, images of flowers based on human-generated data sets and another network that constantly tries to create credible images of flowers using pure image noise – these two work together until the network compiling the flowers actually generates images that can no longer be distinguished from photographic images. We are familiar with this from our everyday lives; these processes are being used more and more in Hollywood productions, for example. Or even when we upload pictures to Facebook and Instagram, which use image analysis software to identify, catalogue, and keyword the people in the pictures.

TS: As far as I know, Photoshop has been on the market since 1988, a good thirty years, in other words. What kind of pictures could this program generate ten or twenty years ago and how is it different today? I’m sure there’s been some technical progress, hasn’t there?

TA: Hard to say, the tool is definitely becoming more powerful all the time. Today, it specializes more and more in the fusion of 3D animation and software-generated images. Photoshop was the ultimate pioneer in creating fake images and has permeated our everyday lives in the form of commercial advertising photography.

TS: What exactly was your approach in the video “Flowers Were Waiting on the Balcony of the Room, So Beautiful!”? I think in a lot of your other works the idea behind them is pretty apparent on the basis of this process.

TA: Well, I told Photoshop to look at the bottom part of the video image, and based on what it could see, create a suitable filling for the top part, which was more or less empty. For every single frame of the loop I created a script, which the program then automated. Photoshop sometimes does this more successfully, sometimes less so, and this generates a lot of flaws and glitches in the video. I applied this process in a different form to all the pictures in the series. So, there is often an original of a photograph that is not alienated, and then there is an iteration in which the software analyses the image, replaces parts of it and rebuilds other parts. In these works, I consciously wanted to give up control, which means that there is a visible post-production process where I just let the program do its thing to a certain extent.

TS: And yet there comes a moment when you reassume responsibility, stop the process, and decide what is worth presenting as an image …

TA: In concrete terms, I have tried to create images in which the software interventions can only be seen after a bit of a lag. I wanted to give the images a certain sense of familiarity. At the beginning, this draws you into the work. Then you look more closely and see what’s going on: Hang on, there’s something completely phoney here and nothing looks the way it should.

TS: The three groups of works we talked about earlier address the phenomenon of iteration – i.e. the process of repeating and picking up on certain forms. How come you think in double images?

TA: A finished work has usually gone through a number of different processes. It may be some- thing that has been photographed two, three, or four times. Or maybe there was actually a photograph out there that was printed out again as a background in the studio and re-photographed. On top of that, there are usually software processes. So, there are many different steps leading into a work, and I have to make certain decisions. There are a lot of steps beforehand and there may be a good many afterwards too. For me, photography is a space of possibilities. Why shouldn’t I explore these options?

TS: To what extent are your work titles a factor in creating these ambiguities? You sometimes number works with 1 and 2 and thus clearly indicate which picture is the starting point and which is the iteration. Do other titles have an open associative space?

TA: In most cases an artistic statement is underpinned by the title. My idea was to post it on social media and describe the work accordingly. In other words, I give the iteration a certain context, a claim. When the pictures in the series “A Miss Is As Good As a Mile” were finished, I actually uploaded them, ran them through some Google image analysis software and looked at what Google thought it could see in each picture. For example, there are terms like “performance”, “stage”, “poster”, “art” in brackets. In the title search, there is thus a predefined narration where, as with the images, I give up control and let the software analyse what it sees.

TS: For the exhibition setting, we decided to put a raw metallic drywall installation in the space. Processes are made visible here too …

TA: Yes, we expose the construction and the physical supports behind an exhibition and gear ourselves to certain industrial standards. There are specific distances between the individual columns, which restrict us in terms of where we position the images. We need to take our cue from these standards but can also circumvent them if necessary.

TS: With “Mirror Mirror” we chose a title that is also an iteration. We have a mirror that generates an image. Another mirror then comes into play, which in turn generates a new mirror image. The question I ask myself is whether there is actually any element in your work claiming the status of an original? Do you still think about, or even consider, the “original” as a category?

TA: At the end of the day, my take on it is this: the print comes in a certain form and a certain number of copies. That’s determined by me. On the other hand, most people who see my works integrate them into other forms. For example, there are image data and exhibition views of these works around and in circulation. So, the image has a second life and is seen on the screens of mobile phones or computers. It’s already another iteration carving out an existence on social media, or simply out there. In other words, there are these physical works along with different instances perpetuated on mobile phones or on the Internet.

TS: Would it be in keeping with your philosophy that all the different instances have equal value as images? Are we perhaps at the beginning of an infinite, automated chain of image generation?

TA: The vast majority of the images we see in the future will probably not be created by humans, but rather by software. It’s all going to be based simply on photographs taken by people in the past. Thus, any supposedly new images we encounter will be artificially created images consisting of old images. This is a future that primarily consists of images created by neural networks. Inasmuch as these networks are only limited in time and by the capacity of the computer when it comes to producing new iterations and new variants, there will no longer be the concept of the authentic original, of photographic evidence, the concept of the credibility of any photographic recording per se or a photograph that is claimed to be constant and no longer subject to change.

TS: Supposing we do actually move into a future where everything we see and consume is completely artificial. Isn’t this an alarming vision?

TA: The more credibly these automatically generated pictures become counterfeit images, the less we’ll be able to see through the deception. As individuals, we will no longer be aware of this step, where we enter a world that is actually 100 per cent artificial. It is quite likely that the photographic will no longer be necessary because nothing will be authentic any more. Probably at some point the networks won’t need any more new material but will generate stuff themselves that is ostensibly new. This is a very dystopian but fairly likely view of our future in terms of the images that will construct our world.